The first services at St Paul’s were accompanied by a harmonium, but an organ was installed in 1868, having been imported by C Russell, an organist; at its first use ‘Mr Russell himself conducted the music, and under his masterly touch the grand tones of the organ filled the sacred edifice with harmony’. A replacement organ was installed over the Christmas period of 1876-77, requiring reconstruction of the eastern wall and apse. Both the choir and the organ moved around the church at various times as the church was enlarged, or as differing opinions of the acoustic benefits of different positions held sway.

The engine of the organ was run by water, and in 1878 the organist failed to turn the water off after playing the organ and ‘inundated’ the houses below the church. In 1920s an electric pump was installed. This organ was removed from St Paul’s in 1964, electrified and installed in the new cathedral, and a small organ, originally purchased by the Cathedral Committee to be a temporary stopgap at the cathedral was installed at St Paul’s. (The current organ at Old St Paul’s was funded through considerable fund raising efforts from the Friends of Old St Paul’s, and installed in 1977).

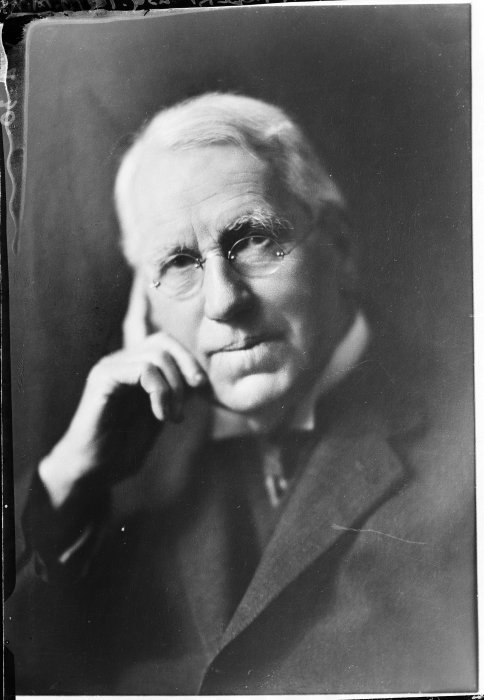

The organist and Director of Music at St Paul’s for almost 60 years was Robert Parker (pictured above). He began his career there in 1878, in slightly inauspicious circumstances – he apparently came to Wellington from Christchurch on the offer of employment from St Peter’s, as well as being conductor of the Choral Society, and presented himself to the church on arrival – but having seen the church, it seems perhaps he changed his mind and decided two days later accepted a job at St Paul’s instead. At his first concert just after taking his position (which the newspaper stated was ‘an unqualified musical success’ he stated that the concert ‘most probably will also be my last’. Rather, this was the first of very many concerts and services held by Parker, who had a profound influence over the church and its music for 50 years. A jubilee service was held for him in 1928, and he continued into his 80s, and played at the consecration of Bishop Holland in 1936.

At first the choir appeared in their own clothes, but from 1879 the men were provided with surplices. Boys were added to the choir in 1879, and the following year the entire choir was in surplices (from which flowed a request for a choir room, which was eventually built in 1883. The women of the choir only received their own separate room for robing in the 1940s). In 1900 the choir was described as being made up of 16 boys and 14 men, with a ‘supplementary choir of ladies at the back of the chancel’.

Two others were crucial in the life of the music of the church – Winifred Upham, who was a chorister at the church of 57 years, and also played the organ at the Tinakori Road Churchroom for 36 years. She and Parker ‘were for long the Grand Old Pair of St Paul’s music’, along with a Mrs Parsons, ‘whose beautiful bird-like soprano delighted congregations until after her eightieth year’. Both Parker and Upham have memorial brasses in the church.

Rev Sprott recorded in 1897 that when he began his time at the church five years earlier he requested that the music be simplified: ‘I took that step, which was somewhat of a sacrifice, on my own part, in the hope that it might lead to a heartier congregational worship. I am bound to day that the result has been somewhat doubtful.’

Almost ten years later he continued to mourn the quality of music and noted that the choir struggled to find enough voices. He wrote: ‘when I think what an uplifting thing the Psalter sung by a large body of trained and devotional voices can be … it is to me a weekly grief that we cannot have it so sung. May of us do not know what we thus miss … Perhaps if we all really began to interest ourselves in it we might at least have psalms and hymns sung in such a way that their music would go with us along the dusty roads of life’.

Despite Sprott’s concerns, music remained a crucial part of the life of the church – concerts were a regular occurrence, and Robert Parker recalled later that the standard of music was so high that people would congregate outside the church to listen to evensong.