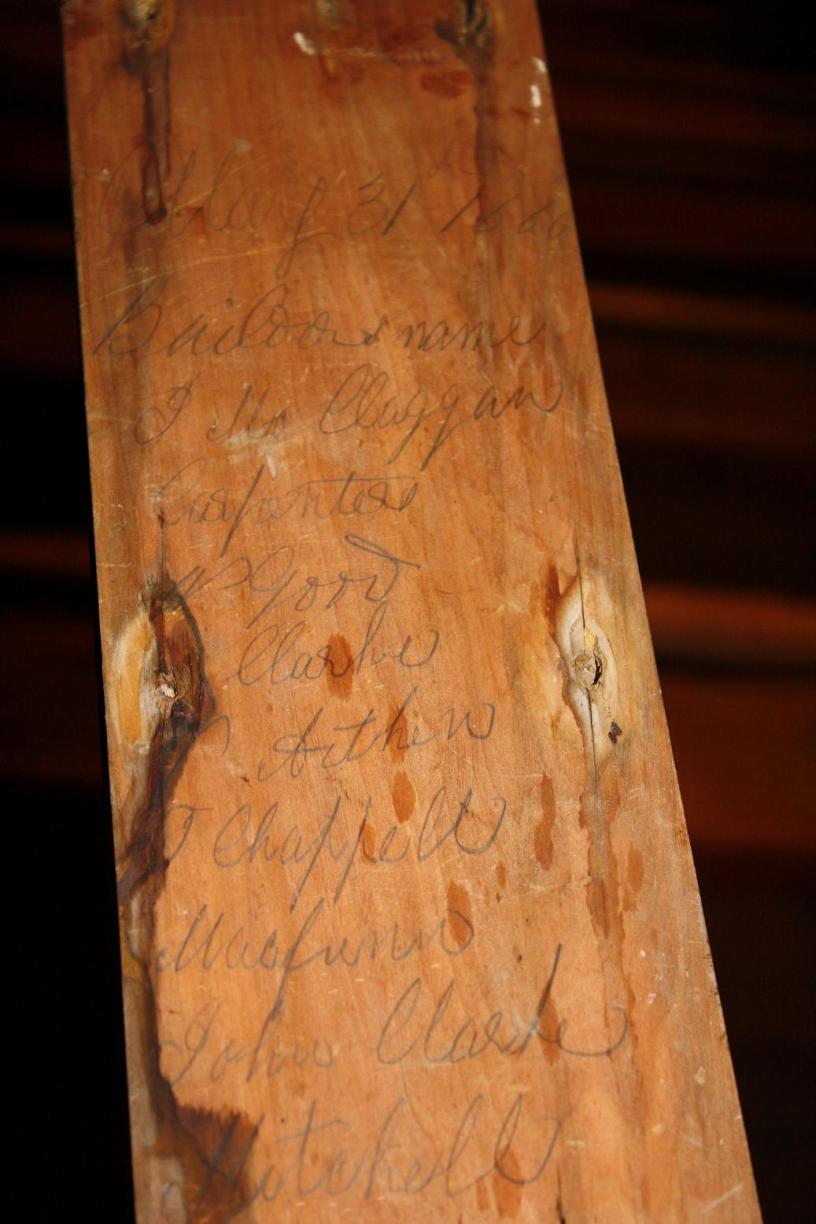

Hidden within a pillar in Old St Paul’s is a piece of wood (pictured at the top of this story), signed with the names of the builder of the church, John McLaggan, and his eight carpenters. It is dated 31 Mary 1866, just before the opening of the church. The board was then closed shut and forgotten, until it was found again almost 100 years later during the restoration of the church. The board is now kept closed, and visitors to the church would not know it was even there. (The names of the carpenters listed on the board appear to read: ‘W. Good, Clarke, W.Aitken, O.Chappell, Mcfunn, John Clarke, Mitchell, William Good’).

John McLaggan

Until recently, very little was known about McLaggan, clearly a skilled craftsman to have built such a beautiful church in less then two years. John McLaggan was born in Scotland in around 1803, and came to New Zealand in the 1840s or 50s, probably with his wife Margaret. He always described himself as a carpenter in Wellington electoral rolls. He first appears in records in 1855, making an unsuccessful tender carry out work on the Lands and Survey Office in Wellington.

Political Career In 1867 he began his brief political career, standing alongside Edward Jerningham Wakefield for election for the Wellington Provincial Council. The Wellington Provincial Council existing from 1853 – 1876, when New Zealand was divided up and governed by six and then later ten provinces, which co-existed with the national General Assembly. The Provinces were powerful, with land disposal policy, public works and immigration devolved to them. Wellington Provincial politics was particularly bitter: as Rev Richard Taylor wrote:

It is generally acknowledged that it is chiefly owing to the high winds, which render the minds of the settlers so irritable, that, were it not for politics, which act as the safety valve for the place, there is no saying what would be the result.

Wakefield was at the time locked in a fierce battle with the Province’s powerful Superintendent Isaac Featherson, and gathered together an odd grouping of working settlers, combined with ‘independent runholders’, in a grouping known as the ‘Radical Reformers’. These ‘reformers’, including McLaggan, won easily in the 1857 election. The Wellington newspapers of the time were deeply partisan and can’t be relied on to give an accurate opinion of their political opponents, so it is difficult to assess his real effectiveness as a councilor, but McLaggan was criticised for his lack of speech-making at the Council: the Wellington Independent wrote ‘Mr McLaggan may as well be an Ashantee or a Patagonaian as far as any can judge by his language, for he takes uncommonly good care not to exhibit himself on the floor’. The Reformers faction quickly collapsed in acrimonious quarrels, and at the next election only one Reformer was elected; McLaggan doesn’t appear to have tried politics again. In the same year McLaggan’s political career came to an end, 1861, he won the contract with his partner Thomson to build the Queen’s Wharf, a very ambitious project to build Wellington a deep water wharf which had been commissioned by the Provincial Council. The challenging work, which was completed in 1863, required McLaggan to bring large amounts of totara over from the Wairarapa. It was made more complex with changes to the plans during the project, contending with the tides, and ships berthing against the wharf while McLaggan was still working on it.

McLaggan was also the city’s undertaker (perhaps for just a short time), a member of the committee of the Wellington Mechanic’s Institute, and owned a saw mill in the Wairarapa while he was building the Queen’s Wharf. He also owned a section in the Hutt Valley from the 1850s, a two storey house on the Terrace (just before the entrance of Woodard Street), where he lived for many years, and later a house on the corner of Cuba and Vivian Street (then called Ingestre Street). He had sufficient funds to leave his brother in Perth, Scotland, a substantial £800 legacy in his will.

Building St Paul’s McLaggan built Old St Paul’s in 1864-66, when he was in his early 60s. The tender was advertised in August 1864, and the foundation stone laid in August 1865 (when the work was presumably already well underway). The church was then completed in June 1866. The Wellington Independent newspaper, which had earlier been so disparaging of McLaggan during his political career was very complimentary of his work:

The work of erection was entrusted to Mr. McLaggan, of this City, and to him, too, we willingly accord the greatest praise for the scrupulous exactness with which he has followed his instructions, and the expeditious manner in which the work has progressed. It seems but yesterday that we saw the rude skeleton of a building standing on a barren roughly fenced spot of ground, and now a handsome Church attracts the attention of the passerby. Mr. McLaggan has verified the good opinion always held of his capabilities, and shown that it is possible to combine speed, strong workmanship, and skill. We congratulate him on the approaching successful termination of his labours.

After St Paul’s Just after the completion of Old St Paul’s, McLaggan, a Presbyterian himself, won the contract to make the wooden seats, pulpit and reader’s desk for the Presbyterian St Andrew’s on Lambton Quay, which was being built by a different builder at the time. (This building was later moved became St Paul’s off-shoot church in Tinakori Road). McLaggan doesn’t appear in the newspapers after this, so perhaps St Paul’s was his last major job. McLaggan’s wife died in 1876.

Four years later his housekeeper burnt to death in McLaggan’s house on the Terrace: she was described as being ‘given to intemperance’, and had been on a drinking spree for 10 days when she accidently set herself on fire. The newspapers provided gruesome accounts of her death. McLaggan died in 1886, at the age of 83, while living in his house on Vivian Street; his death was barely reported, and the only description currently found in a newspaper described him simply as a ‘very old settler’. He was buried with his wife in the Bolton Street Cemetery.

Photo: Heritage New Zealand. Sources: Brad Patterson, ‘Would King Isaac The First Lose his Head: The power of Personality in Wellington Provincial Politics 1857-1861’, Journal of New Zealand Studies, March 1996, pp2-16

One of the builders shown on the board was my ancestor: William Aitken. According to his obituary in The Evening Post (accessed through Papers Past) he was born in Scotland in 1814 and emigrated first to Melbourne before arriving in Wellington in c1855. In partnership with John McLaggan, he built the old Courthouse, the Bank of NZ on Lambton Quay, old St Pauls and many other buildings. He died in 1895 and was also buried in Bolton St along with many of his family. It is very exciting to see his name written.

Thanks for your comment Susan. It is interesting to see that William Aitken got a lengthy obit, but John McLaggan didn’t when he died. I really appreciate you taking time to write in, Thanks, Elizabeth

Hi Susan,

William Aitken was my great great grandfather and I’ve only really discovered this family connection in the last couple of years. His son John was my great grandfather. I’ve found William’s grave in the Karori Cemetery (reinterred from the Bolton St cemetery) and given it a good clean up.

I have found out a little about Williams daughters but there are many gaps. I’m keen to stay in touch and exchange any information that would be of interest to you.

Best regards,

Bede